Portland is weird. We like it that way! That weirdness can show up in our beekeeping too. We have weird hives and a weird way of doing things. For example: I use Langstroth hives, but I run all mediums (or westerns, as many people call them here). I don’t use foundation and I don’t treat my bees with acaricides. And I’m not the weirdest. Many of our members use top bar hives or Warré hives.

Every year there are more and more beekeepers being added to our ranks in this backyard hobby and we love that. They often choose from the many options of alternative (“weird”) hives. Unfortunately, there are very few options for these beekeepers to source bees. They have to buy packages that just don’t show any qualities of surviving in our area and are inherently problematic. Or they try to catch swarms, which is getting increasingly competitive each year. It’s also not a sure bet of getting good bees, or even any bees at all as they find it difficult to keep up with the more experienced beekeepers.

What we need in Portland is a source of locally raised bees that can accommodate all our weird variety of preferences: top bar, Warré, western Langstroth, small cell, treatment-free, foundationless, or whatever the personal flavor may be. The problem is, it’s difficult and costly for a large operation to begin and do well. Not only due to the “weird” market of buyers, but our later queen rearing season followed by a short-lived nectar flow can add to the challenge too.

Since we have such a large club with a relatively high beekeeper density, we have the opportunity to do something really weird: we can be our own bee breeders. Rather than rely on large commercial breeding outfits that either can’t fully meet our large demand or deliver us bees that just don’t do well in our environment, we can work together like bees in a hive and provide for each other. But we’ll have to do it differently. It can be done on a small scale too.

The key to all of this is creating resource hives and overwintering nucs.

For the benefit of the beginner beekeeper, a nuc (pronounced “nuke”) is short for “nucleus hive” and just means a small but fully functional working colony in a small hive configuration. Typically sold to beekeepers in deep 4 or 5 frame Langstroth boxes. They can be made up by the beekeeper themselves instead of buying them, and can be built into whatever hive configuration you prefer. For example, if you’re a top bar beekeeper you can make a top bar nuc. Pretty simple really.

There are many ways to make up nucs by splitting hives. I recommend reading up on the various methods at Michael Bush’s website. The method and timing you use really depends on what your goals are.

- In the early spring (around mid to late-April depending on the weather)

- To replace winter losses

- Sell to other beekeepers

- In the late spring or early summer, during the nectar flow (May or June)

- To raise queens

- Create backup resources

- Prevent swarming

- In the late summer or early fall, after the flow (July or August)

- To overwinter nucs (prepare for winter losses)

There are significant advantages to making nucs during the flow. It’s easier. The bees are less defensive and not easily upset by all the manipulation that will be going on. The weather is nice and there is plenty of food available, so they’ll grow faster and are easier to take care of. Of course, they also may grow very fast and outgrow their little space. So it’s a good idea to also use them as a resource for other hives. (Hence the name “resource hives.”) They can provide additional or backup building materials for other hives that are weak or that you just want to give a boost.

They can provide a spare queen in an emergency. Additional brood. More honey or bee bread (pollen). Or even provide fresh clean comb for a hive that has old comb you’re rotating out. Taking from the nuc’s resources and giving to the larger honey producers can keep the nucs small and manageable and give the larger hives extra help. But of course, whenever taking resources from any hive, always do so responsibly so as not to completely disable the colony.

So what does this all mean for a Portland beekeeper? How is this going to help us?

We experience significant losses in our apiaries every year. On average, about 50%. Most of us are always playing catch-up and trying to make up for our losses by either buying more packages, sometimes nucs if our equipment matches, or by chasing down swarms. These replacement bees then spend the first year building up and we’re not going to get a honey harvest from them. That’s fine. Let them do their thing and we’ll get honey in their 2nd year. But, then we still lose half of them again their first winter and we’re back again to making up the losses. And round and round we go.

Instead of always chasing our tail and trying to right the wrongs, we can just plan for the losses. If I want to have 3 or 4 hives in my apiary in the spring, then I’ll go into winter with 6 or 8 hives. That way, when I lose half of them, I won’t be on that merry-go-round. I’ll be right where I want to be. Providing space for 6 or 8 hives might be problematic though. And it could double our work-load. But that’s the beauty of nucs. Their compact size means they take up less room, are easier to manage, and don’t look intimidating to the neighbors.

So instead of making up nucs in the spring to try to fix our losses, raise queens in a few small queen rearing nucs in the summer when it’s easy. When the nectar flow is over, split some hives to make up some smaller nucs and use the queens you raised earlier. Be sure they have enough food stores to make it through the fall and winter. There may even be some leftover honey for you to harvest. Then, if they survive the winter, they’ll have proven that they are “survivors” and can help improve the local bee population.

Beekeeper A had 2 hives in the summer, and lost 1 hive in winter. In an effort to make up for his losses he split it into 3 parts in late April. The hives re-queened themselves successfully and built up well, but due to the setback caused by splitting, none of the hives built up enough to provide a honey harvest.

Beekeeper B had 2 hives in the summer. She took a comb of eggs and some nectar/bee bread from each one in June and used 2 small nucs to let the bees make queen cells. After the queen cells were formed she divided them up into 4 small queen rearing nucs to let the new queens emerge, mate, and begin laying eggs. She successfully raised 4 new queens which she used in August to split up her 2 other hives and their resources to create 6 nucs to overwinter. She lost 3 of them in winter, but the surviving hives built up quickly in the spring and had a strong workforce ready to take full advantage of the nectar flow.

While these 2 examples are idealized hypothetical situations, they illustrate how we can use the natural cycles and seasonal growth of the bees to our advantage and plan ahead. The nucs that overwinter grow extremely fast. The photos on the left show how one of my nucs grew from an overflowing 5-over-5-frame nuc to fill five 10-frame boxes in just 3 months. Swarms and packages cannot do that. Even nucs built in April can’t do that. They have too late of a start. Overwintered hives are building and gearing up for this in February. They have a 2 month advantage.

Maybe Beekeeper B above doesn’t want 3 hives. She can sell the 3rd one and provide a high quality, locally raised source of bees for another beekeeper in her club. And maybe she has some kind of weird hive configuration that her friend also has.

The challenge –

I encourage the beekeepers in our club to take up this challenge and plan ahead for losses. Build or purchase some nuc configuration that fits your beekeeping style and start small. See if you can raise a queen or two. Make up a couple splits in the late summer and see if you can get them to overwinter. It’s a learning and experimental phase, so don’t be too concerned about doing it wrong or making mistakes. That’s how we learn. We can then take the data from these experiments and improve year over year. Let’s work together on this and see if we can figure out the right formula for getting nucs through the winter so we can stop chasing our tails.

Resources to get you started:

Michael Palmer – Importance of getting local queens (YouTube)

Michael Palmer – On Package Bees (YouTube)

Michael Bush – Bee Splits (bushfarms.com)

Michael Bush – Nucleus Hives (bushfarms.com)

Kirk Webster – Cell Building and Overwintering Nucs (kirkwebster.com)

Splits & Nucs Demonstration (pwrbeekeepers.com – PDF)

Double Nuc Instruction (betterbee.com – PDF)

Establishing Honey Bee Colonies in Cold Climates (umaine.edu)

Overwintered Honey Bee Nucleus Colonies: Big Solutions in Small Packages (oregonstate.edu – PDF)

I’ve been trying to do exactly this and hope to have some TB nucs this year. Has anyone done the cut down method of queen starting?

You can get double nuc equipments from http://www.dadant.com/catalog/8-frame-equipment . This helped me a lot in every stage of beekeeping. This may help you in guiding your problem.

This is a great article and something I would like to try. I’m just in my second year of beekeeping and I did loose 1 of my 2 hives over winter. It would be great to have someone guide me through the process as the season progresses. Two things I’m confused about after reading the article.

1. The slide images show 2 nucs on top of 1 ten frame deep. How does that work. Don’t the worker bees intermingle that way and potentially kill the queens? I was imagining the resource hive would be double deep nucs.

2. One of the photos showed resource hives set up as 2 4-frame nucs inside a 10-frame deep with a divider in the center. Does this work just as well as the other setup. Is there anything different that needs to be done to manage it?

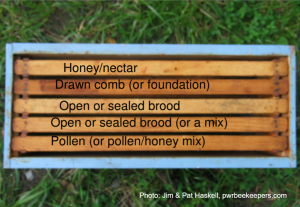

The “resource hive” in slide 2 has a ten-frame deep on the bottom with a divider board as shown in slide 14. The bees cannot intermingle.