The Reason Behind Honey

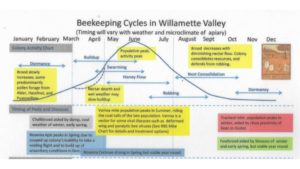

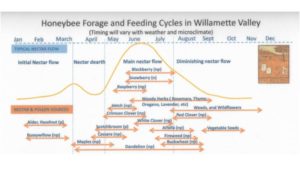

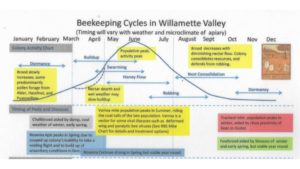

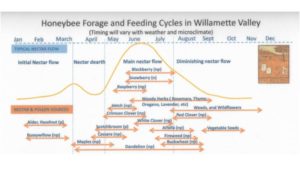

It’s no secret that honey bees are wholly unique from our 4,000 North American bee species. The main difference is the size, scope, and intricacy of their social system. The superorganism life history strategy bestows certain benefits to Apis mellifera, who use their vast colony numbers and communication systems to maximize collection and use of the pollen and nectar resources of their environment. Just as blooms have seasonal cycles, so do honey bees, and these 2 cycles are indelibly linked as shown in the diagrams from Ruhl Bee Supply below.

While solitary and small social-colony bee species have some form or caste that hibernates through the winter, honey bee colonies actively survive through the cold months by clustering inside the hive and generating heat by vibrating their flight muscles. This is fueled by the spoil-proof and sugar-rich substance we know as honey. To ensure survival and reproduction of the colony as a whole, the spring months are spent building up their populations enough to swarm, and summer months are spent preparing for winter. At each stage in the warm season they must adjust their behaviors to maximize their workload to either collect as much pollen as they can to build their population, or to collect as much nectar as they can to turn into honey.

Where we fit in

As the responsible honey bee stewards we are, every time we open our hives, it is important to consider exactly what the colony should be doing at that point in the season. Summer is stressful for the bees. This is when nectar is scarce, they must defend their hive from robbing bees and yellow jackets, Varroa populations spike, and they must keep their hive cool. Additionally, colony populations are at their densest, and hive inspections can disrupt their primary goals in favor of cleaning up the mess the beekeeper left behind. It is important to go into each inspection with a goal in mind; once you’ve satisfied your goal, close up the hive and move on.

Summer and the nectar dearth

Unfortunately, the nectar dearth is here. We were hoping that this year we’d see blackberry in bloom through July, however it is becoming apparent that will not be the case. It is now that we can begin to predict whether a hive will survive the season or the winter with a higher degree of accuracy. Weak hives can be diagnosed by having low honey stores, signs of robbing, and high mite populations. Depending on your personal management philosophy, each of these hallmarks can be responded to in order to increase their chances of survival.

Feeding

Low honey stores can be responded to by feeding. It is important to remember Boardman entrance feeders can draw robbing bees from other colonies or yellowjackets to the hive. So, break out an internal-hive feeder of your choice if your bees need a hand building up their honey stores. Additionally, move from your 1:1 sugar:water syrup ratio to 2:1. This will help them dehydrate their stores more quickly and with less effort, and will prevent too much moisture in the hive during the winter.

Robbing Prevention

Robbing can be diagnosed a few ways. The first warning sign would be remnants of warfare- large numbers of dead bees at the entrance of your hive. If you’re lucky, you may see robbing bees before this point with large numbers of bees landing on, buzzing around, and sniffing out cracks and other areas of the hive body. Foreign bees are not familiar with your hive’s entrance, but it is only a matter of time before they find it. Robbing must be responded to immediately! As soon as there are any signs, equip your hives with entrance reducers or robber screens to give your guard bees a much needed edge. These tools are also useful for preventing yellowjacket predation, which is also picking up at this time–if you haven’t broken out your yellow jacket traps yet, do it now!

Monitoring Varroa

Now, onto the lengthy topic, and bane of the modern beekeeper’s existence…Varroa mites. Regardless of your treatment philosophy, mites must be monitored and dealt with in an urban setting, where there are many managed hives in a small area. July is when we begin our more diligent mite sampling efforts. There are many ways to sample your hive for mites, though the ones I use most frequently are the sticky board method with screened bottom boards, ether rolls, or alcohol washes (if you don’t have a mite sampling kit, or don’t want to make your own, pick one up at the next PUB meeting).

Jar methods of sampling like ether rolls and alcohol washes tend to be more accurate than sticky boards. To perform these methods, collect nurse bees from the heart of your brood nest (with extra care not to collect the queen!), in a quart jar. I recommend a 300 bee sample, which is about ¾” in the bottom of the quart jar. For an ether roll, use a solid lid and spray automotive starter fluid (ether) for about 2 seconds. Then swish your bees around the inner walls of the jar, and the mites will stick. From there you can count the mites, and you can determine the ratio of infection. For an alcohol wash, drown your bees in isopropyl alcohol, and equip your jar with a mesh lid. Strain the liquid out of the jar over a coffee filter, and count the mites left behind to determine your ratio.

It is generally agreed upon that a colony with 3,000 mites cannot survive (Source). If you find 9 or more mites from your 300 bee sample, it is time to react. If you subscribe to use of chemical treatments, this would be the time to use them. If you do not use chemical treatments, my go-to response is to induce a 3-5 day brood break by caging the queen. Other options would be to re-queen if you suspect the issue is weak genetics (take context into account here- is it the genetics or external environmental factors causing the mite-spike?), add a frame of capped brood from another hive to spike the colony population, decrease hive cavity space (Source), or sift powdered sugar onto your bees to encourage them to groom (only do this if you have a screened bottom board). If the mites persist, this is the time you would choose to experiment with a treatment of your choice, or to do the hard task of killing your colony with soapy water before they spread the mites and diseases they vector to other local colonies.

Even strong colonies can be affected by high mite populations at this time; strong bees pick Varroa mites up from the weak bees during robbing, and bring them back to their hives (Source). It is of utmost importance at this point in the season to monitor and respond to mites regardless of your personal treatment philosophy. Keep in mind, it is often the viruses that mites transmit rather than the mites themselves that are directly responsible for a colony’s demise (Source). During inspections, keep your eyes open for Deformed Wing Virus, K-wing virus, and Sac Brood.

It’s not you, it’s them

It should be noted that even the most diligent and responsible beekeepers can end up with dead colonies. My best advice would be to pay attention to your bees. Allow them to take care of the problems they can handle, and when they can’t, take mindful action. Each beekeeper must craft their own management philosophy, which often entails combining elements of many separate doctrines. So long as you are responding from a place of knowledge, experience, and good intentions, you’ll be doing a service to yourself, your bees, and the greater good.