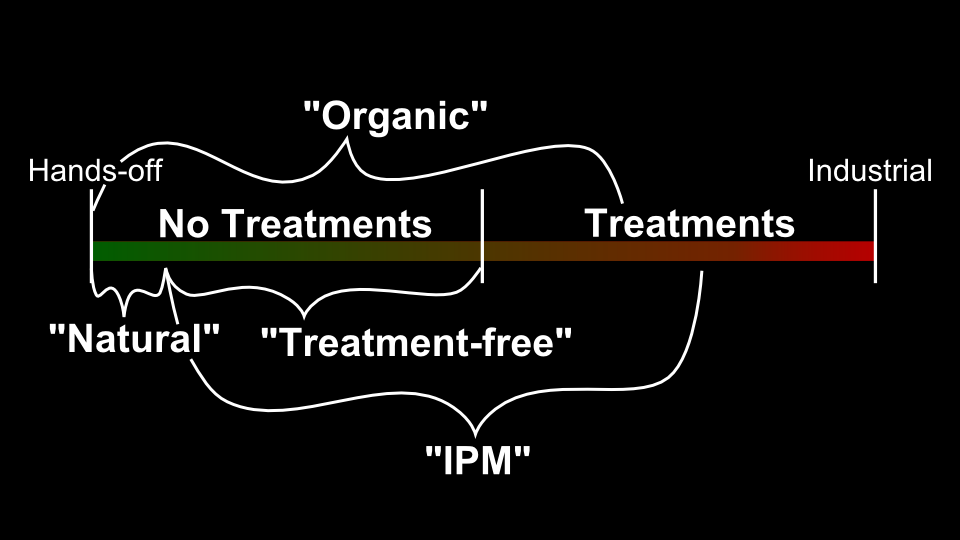

When new backyard hobby beekeepers are seeking out advice and learning how to keep bees, they are often confronted with various models of beekeeping. The 2 main schools of thought are either “natural” or “conventional.” Due to the usual practice of dosing chemicals into a hive, many hobbyists are turned off to the conventional method and instead seek to do things the “natural” way. Unfortunately, the “natural” way also has many sub-partitions. In fact, there’s a huge spectrum of methods and names outside the “conventional” way. Each having a subtle distinction that sets it apart from the others.

“Natural” – Since beekeeping involves putting bees in a man-made box, on the ground, with removable combs, there’s not much that’s really natural about it. But some people practice a mode of beekeeping where they just let the bees move into a hollow log. They basically provide habitat for the bees and don’t do any manipulations to the hive. This is as close to natural as you’re going to get, but it occupies a very narrow band of the spectrum.

“Organic” – This label is often used by many who intend for it to mean, “As nature made it.” It used to mean, “No pesticides.” But the name has lost meaning as “organic” pesticides have come to market and can be used in place of synthetic compounds. In other words, you can keep bees in a log, never touching them, or use naturally occurring, lab-purified chemicals in concentrations far higher than can actually be found in nature, and both can be called “organic.”

“IPM” – Integrated Pest Management. This covers a very wide range of practices, including pest control methods “to manage pest damage by the most economical means, and with the least possible hazard to people, property, and the environment.” (1)

“Treatment-free” – This is the principle in which no treatments are used. That is to say, nothing is introduced to the hive by the beekeeper with the intent to kill a pest or treat disease. Let the bees deal with it on their own. However, this doesn’t mean a treatment-free beekeeper does nothing. And this is different from “natural” for reasons I’ll get into in this article.

In order to fully understand what treatment-free beekeeping is all about, it’s important to understand the pros & cons of treating and not treating. There are benefits and risks to each.

Treatment: Pros –

- Minimize losses

- Stop the spread of disease & pests

All beekeepers actually want to do this, but conventional beekeepers feel the best way to do this is with chemical intervention.

Treatment: Cons –

- Propping up weak genetics

- Treatment-resistant pests/disease

- Chemical contamination & synergistic affects with other chemicals (2)

Michael Bush goes into great detail about all the problems with medically treating bees and the reasons why this is a bad idea. But to sum up, it’s an unsustainable model. It supports weak bees and promotes stronger disease and pests. Also, many of the chemicals used in the hive can build up in the wax combs and/or magnify the toxicity of pesticides or fungicides used in agriculture that the bees are exposed to. (3)

Slightly off-topic sideline

Let’s take a quick diversion and cover the more popular treatment options and explore their problems from the perspective of a treatment-free beekeeper. Of course, they all promote bad genetics that rely on beekeeper intervention to survive, so we’ll just get that one out of the way.

Mechanical treatments:

- Powder sugar dusting – Impractical with a large operation or for a beekeeper with a busy schedule.

- Drone “trapping” or removal – Will this breed mites that seek out worker larvae?

- Brood breaks – No major objection. It would be preferred that the bees do this themselves without assistance.

- Screened bottom boards – Many don’t consider this a treatment, but some do. This has questionable effectiveness.

Chemical treatments:

- Apiguard (25% thymol) – Lipophilic, meaning it builds up in the wax

- ApiLife Var (74% thymol) – Lipophilic

- ApiVar (amitraz) – Synthetic; strong synergistic effect with fungicides (3)

- Apistan (fluvalinate) – Synthetic; mites are resistant to it now

- Checkmite (coumaphos) – Synthetic; mites are resistant to it now

- MiteAway Quick strips (MAQS) (formic acid) – no major objection aside from promoting bad genetics

- HopGuard (hop beta acids) – shown to not be effective

- Oxalic Acid – fumigation is hazardous; drip method is done in the winter and could freeze the bees in some regions

- Mineral Oil fogging – causes fires

- Essential Oils – inconsistent concentrations & formulations make kitchen chemistry difficult and hazardous to the bees

Back on topic

Treatment-free: Pros –

- Breed stronger bees

That’s really the ultimate goal. Instead of trying to help weak bees, the idea is to use natural selection to decrease losses over time with less beekeeper input. The key to treatment-free beekeeping is to artificially increase the natural reproductive process of the hives. This is what sets it apart from “natural” beekeeping. Instead of letting the survivors swarm and reproduce on their own, they are split or queens produced to make more offspring than they otherwise would have.

Treatment-free: Cons –

- High losses

- Spreading disease & pests

These are the criticisms often lobbed over at the treatment-free beekeepers. They are often told, “Your bees are just going to die,” or “You’re infecting our hives with your diseases.” Of course, treatment-free beekeepers fire back with something like, “Your inferior drones are mating with my queens,” and thus the battle rages on. But what can be done to deal with these arguably accurate claims?

Dealing with loss

You’re going to lose hives. It’s inevitable. Of course, treating hives isn’t a guarantee of survival either, but at least doing something about it can make you feel like you tried. So if you aren’t going to apply treatments, then instead plan for the loss. Make more hives than you really want. Plan for about 50% loss, so double the number of hives you want before winter. If you want to have 2 hives in the spring then go into autumn with 4 or 5. Having more small hives is easier to manage than having a couple really big ones. If you luck out and more survived than you planned, then sell the extras. People in your area would love to have a strong hive that survived the winter.

Also, keep perspective on the whole thing. Losses can be hard if you are attached to them. But this is just nature’s way of removing the bad genetics from the area.

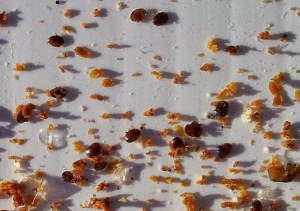

Dealing with disease & pests

So your hive gets over taken with Varroa mites, what do you do about it? Well, you can do nothing and just let them deal with it on their own. But there’s a great concern about pest transmission to other hives in the area. This is the main point of criticism with treatment-free beekeeping. It’s not so bad if your hive dies if the disease and pests are contained. But if you live in a densely populated area of beekeepers, the mites that got out of control in your hive might be spreading to the neighbors’ hives.

Can you isolate your apiary? If no other hives are within a 3-4 mile flight radius, you’re probably fine. In an urban area, this may not be possible.

So what can a treatment-free beekeeper do about this?

Treating the hives has a similar negative affect to the neighborhood by “infecting” it with bad genetics. Drones from the treated hives will spread their inferior genes. Is there a middle-ground that will satisfy both groups?

At the OSBA conference in Seaside, Oregon last November, Dr. Dennis vanEngelsdorp, with the Bee Informed Partnership, gave a talk on “Management Practices that Work and Those that Don’t.” Unfortunately the content of his presentation doesn’t seem to be online, but in it he presented a plan that might be a good compromise that would settle the battle between those who treat and those who don’t.

- Take mite counts

- Treat the hives that have high mite loads

- Kill the queens in the treated hives and use the bees for something else

Wait a minute! But this requires treating, which goes against the treatment-free philosophy!

Right. But, the objections to treating are:

- It promotes bad genetics

- It contaminates the hive

- It breeds treatment-resistant mites

1) The queen is getting removed. Her genetic line ends. 2) If a suitable treatment is used that knocks the mites out without contaminating the hive, then no harm done. MiteAway Quick strips (MAQS), for example, may be a good option. It’s formic acid that evaporates away with no permanent residue and has shown to be quite effective at reducing mite loads. 3) If done infrequently or alternating with another type of treatment, there’s little risk to creating super mites.

Once the bees are relatively mite-free and the queen removed, these bees are available to be put to use in other ways, such as queen rearing or combining with a weak hive. Instead of just letting the colony slowly dwindle away and potentially infect your other colonies, the problem can be dealt with swiftly and the work force isn’t wasted.

If beekeepers that practice treatments can also follow the same practice of killing the queens with the high mite loads, then they too will be doing the neighborhood a favor of ridding the area of the weak genetics.

As a treatment-free beekeeper myself, I’m giving some considerable thought to this idea and keeping an open mind. I resisted it at first, but the more I think about it, the fewer objections I have. What do you think? If you are a treatment-free beekeeper, do you have any objections to this idea? Please leave a comment below and let me know what you think.

References:

1. Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Principles

2. Drug Interactions Between In-hive Miticides and Fungicides in Honey Bees

3. Acaricide, Fungicide and Drug Interactions in Honey Bees

Other resources:

Michael Bush – The Practical Beekeeper

Kirk Webster – New/Old Beekeeping Discoveries

Dee Lusby – Organic Beekeepers

Les Crowder – For the Love of Bees

Laurie Herboldsheimer & Dean Stiglitz – Golden Rule Honey